A War Fought with Unusual Weapons: How Prussia Used Finance and Politics to Force the Habsburg Hereditary Lands Out of the German Confederation

23. März 2024

Ever since the French Revolution, at the very latest, the European bourgeoisie had been dreaming of the nation-state. The problem was that the old order was by no means organized in such a way as to align with this concept. Germany, for example, was defined by language and culture. But how did the Habsburg hereditary lands fit into this? After all, the emperor had been a Habsburg for centuries. And yet, this dynasty also ruled over Bohemia and Hungary, Lombardy, Venice, Dalmatia, Croatia and so many other countries that neither used the German language nor followed German ways of thinking. For the House of Hohenzollern, this was an excellent argument for eliminating its rival in the struggle for German hegemony. That is why Prussia was in favor of the so-called “Lesser German solution”, i.e. the creation of a German state that would not include Austria.

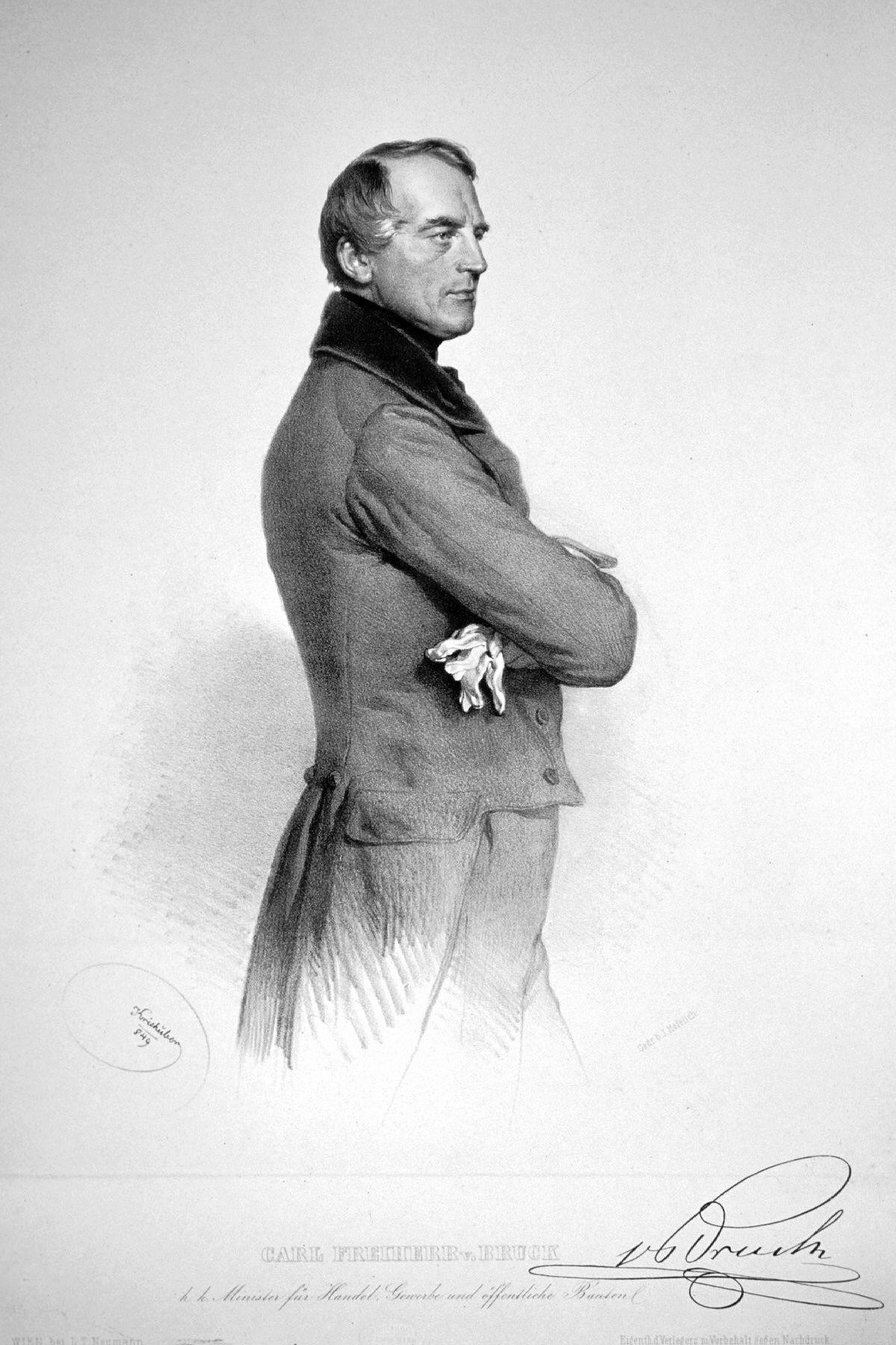

Karl Ludwig von Bruck, the mastermind behind the Vienna Coinage Treaty. We chose not to depict Emperor Franz Josef I at this point, who is shown on the coins, but the liberal politician Karl Ludwig von Bruck. Born into the family of a bookbinder in Elberfeld (now Wuppertal, Germany), he worked his way up from a merchant’s position to become Austria’s finance minister. He could almost be described as a beacon of hope for Austrian economic policy. It was tragic – and not just for him personally – that Franz Josef “ungraciously” dismissed him in April 1860 on false suspicions. The then 61-year-old took his own life. This deprived Austria of an imaginative politician who might have prevented its economic marginalization by Prussia.

The German Customs Union as a Milestone on the Road to Prussian Supremacy

The medium-sized states of Bavaria, Hanover, Saxony and Württemberg were in favor of the “Greater German solution”, and thus wanted to include Austria in the new state. The reason for their position was that the dispute between Prussia and Austria resulted in them enjoying much greater freedom. In addition, Bavaria and Saxony in particular were no longer able to control smuggling on their borders with Austria and Austrian Bohemia ever since the (Lesser) German Customs Union had been established in 1834 on the initiative of Prussia. Real conflict, however, only arose on the subject of protective tariffs. Prussia, which was heavily industrialized, was against protective tariffs while the medium-sized states were in favor as they hoped that tariffs would protect their domestic industries. So Prussia quit the Customs Union and declared that it would not sign another treaty unless the medium-sized states dropped their support for protective tariffs.

The Austrian ministry of economic affairs took advantage of this situation and invited the parties to Vienna in January 1853 to discuss the creation of a Greater German Customs Union. This put pressure on Prussia. In an alliance with the Habsburg Empire, the southern German states would have formed a stronger economic bloc than the northern states under Prussian leadership. Had it not been for the foreign policy situation – Austria had to be prepared for the Crimean War to break out at any moment – this scenario might well have materialized. But faced with this imminent danger, the Habsburgs did not push the matter. Although the Habsburg hereditary lands did not become a full member of the renewed customs union, they at least became an equal partner. In addition, the treaty of 19 February 1853 stipulated that a coinage treaty (Münzkonvention) was to follow within the same year.

The Austrian Coinage Act of 1852

The problem was that hardly any coins circulated within Austria, only banknotes at a fixed exchange rate. Gold and silver coins were minted exclusively for foreign trade. Austria therefore had to put its own house in order before it could think about an international monetary treaty. Thus, on 31 July 1852 an Austrian coinage act was passed, which set a fineness of 900/1000 for the new coinage, a requirement that was in line with the currencies of neighboring southern German states. Double guldens (= konventionstaler, i.e. talers that were minted according to the standard of the new coinage act), gulden and 20-kreuzer pieces were produced.

The Vienna Coinage Treaty

At the same time, the Prussian experts argued with their Austrian counterparts about whether the coins should be produced according to the silver or the gold standard. Of course, this did not mean that they planned to issue only silver or only gold coins. The question was whether the currency should be linked to the price of silver or to the price of gold. Since Vienna expected the gold price to plummet in the future – especially as rich gold deposits had just been discovered in California – the Austrians tried to make the case for the gold standard. In this way, they hoped to be able to pay off their high national debt with cheap gold. Prussia, however, was not interested in a strong Austria and successfully pushed for the silver standard. According to the new treaty, gold ducats worth 4 1/2 gulden were not allowed to replace banknotes in Austria. They could only be used for foreign trade – and even this special permission was to be revoked in 1865.

A bitter pill to swallow. But for Austria, it was a sacrifice worth making to gain access to this common economic area. And so, on 24 January 1857, the Emperor signed the Vienna Coinage Treaty.

Contemporary illustration of the correspondent of the Illustrated London News of 16 June 1869

The Trauma of Solferino

Therefore, Austria began to withdraw banknotes from circulation to replace them with silver coins. However, the next disaster was already on the horizon: the French emperor supported the Italian national movement led by Vittorio Emmanuele. Of course, his reasons were not altruistic. The fact that Savoy and Nice are part of France today is due to his intervention in this conflict. And that is why, on 21 April 1859, Austria had to stop withdrawing banknotes as it had to finance the war in northern Italy. Thus, banknotes circulated at a fixed exchange rate once again.

The war was over quickly. It ended with the Battle of Solferino on 24 June 1859. This battle was a trauma for Austria and a personal defeat for Franz Josef I, who had taken command of the army and had to watch helplessly as his troops were slaughtered in one of the bloodiest battles of the 19th century. 30,000 soldiers were killed or wounded. Even more tragic were the 40,000 casualties who fell ill after the battle due to a lack of bandages, food and water. The Red Cross and the Geneva Convention owe their existence to the international horror at the horror of Solferino.

Prussia, however, rejoiced at the outcome. Having lost its territories in Upper Italy, Austria’s economic power was reduced. Moreover, Austria was also forced to withdraw from the Vienna Coinage Treaty as it was unable to replace its paper money with coins.

Königgrätz and the End of the “Greater German Solution”

In 1865, Prussia pulled off its next coup. It cancelled the old trade agreement between the German Customs Union and Austria and drew up a new one on significantly worse terms for Austria. It made Austria a foreign country for customs purposes.

This was another blow that led to the Habsburgs being lured into a trap when Bismarck deliberately broke the law to provoke a war against Austria. The Battle of Königgrätz established what had become clear over previous decades: Prussia had defeated Austria in the struggle for German supremacy. The “Greater German Solution” that was to include Austria in the German territory was no longer an option, and the Prussian ruler was in a position to elevate himself to the position of German emperor.

After Königgrätz, Franz Josef almost lost Hungary as well. He kept it only because he decided to split up his empire. Whereas it had previously been administered from Vienna, the territories of the Habsburg hereditary lands were divided into Cisleithania and Transleithania. These names came about because the Leitha river, some 180 kilometers long, ran roughly along the border between the two parts of the country. In Cisleithania, Franz Josef ruled as Emperor over Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Gorizia, Carniola and Galicia; in Transleithania, he ruled as King of Hungary over Transylvania, Croatia and Slovenia. The famous Dual Monarchy was born.

This change can be clearly seen in the coinage. Whereas small coins previously bore German legends and gold coins Latin inscriptions, the Hungarian government decided to use Hungarian symbols and the Hungarian language. Issues for Cisleithania, on the other hand, mostly featured Latin inscriptions or no legend to reflect the multilingualism of the various territories.

A Member of the Latin Monetary Union?

After Austria’s access to the German economic area was blocked, the country tried to align itself with France. They discussed joining the Latin Monetary Union. In fact, they had already agreed on a final draft of the treaty, but it was never ratified. Nevertheless, Austria-Hungary decided to issue gold coins worth 20 francs, or 8 gulden. Although there was no formal obligation to accept these coins in the countries of the Latin Monetary Union, they were compatible and could therefore circulate in these areas. What made these coins particularly important was that they became the customs currency of the Dual Monarchy. This meant that anyone importing goods into Austria had to pay customs duties in this currency.

The Transition to the Gold Standard

In the late 1840s, the Austrian government had hoped to get out of its debt with cheap gold-based money, but the huge silver discoveries in Virginia City, Nevada in the 1860s had led to a worldwide depreciation of silver. So when Austrian politicians wanted to stabilize their currency system in the late 1880s, they decided to introduce the gold standard. This resulted in the introduction of the currency of the “krone”, the specifications of which were laid down in the act of 2 August 1892. On 1 January 1900, the krone was to completely replace the gulden.

When Emperor Franz Josef closed his eyes forever on 21 November 1916, the krone was still the Austrian currency. It was only replaced by the schilling on 1 March 1925 due to the inflation caused by the First World War.

To see all the coins of the Tursky Collection that will be auctioned on 26 March 2024, visit our eLive Premium Auctions at www.kuenker.de/en