The Hero of the Second War of American Independence

14. January 2017

When the Congress of the United States of America wants to bestow a particularly high honor, it awards the Congressional Gold Medal. It does so since 1775, when General George Washington was decorated this way. Since that time, many distinguished honorees received this medal. The recipients include Neil Armstrong, Winston Churchill, Walt Disney, Thomas Edison, George Gershwin, Ulysses Grant, Martin Luther King, Charles Lindbergh, John Pershing, Frank Sinatra, Mother Theresa, John Wayne, and the Wright brothers. Among them was Alexander Macomb praised by his contemporaries as the Hero of Plattsburgh.

Alexander Macomb. Oil painting by Thomas Sully.

Alexander Macomb

Alexander Macomb (1782-1841) started a career as an officer when he was only 16 years of age. After gaining some practical experience, he was among the first students who studied at the Military Academy at West Point. Following graduation, he supervised the fortifications at the coastlines of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia for five years. He continued this activity until the so-called Second War of American Independence broke out.

The Second War of American Independence

To get to the bottom of the so-called Second War of American Independence, it is necessary to return to Europe. Great Britain was fighting against Napoleon. To bring France to its knees, the maritime power had imposed the so-called Continental Blockade. To prevent the French ships from calling into the American ports, the British fleet monitored the American coast and took the liberty to control all ships, which wasn’t always accomplished in a peaceful way. During inspection of the USS Chesapeake, 21 seamen were killed, wounded or displaced.

And that constituted the next bone of contention between the British and the Americans. The Royal Navy forced American seamen to serve in the British fleet. For example, 22 of the 663 crewmen on Nelson’s Victory are said to have been American citizens.

Considering that some American politicians regarded the temporary weakness of Great Britain a splendid opportunity to conquer Canada, it is hardly surprising that President James Madison declared war on the United Kingdom on 1 June 1812.

Burning of Washington by the British. Wood engraving 1876.

The Battle of Plattsburgh

A little bit too complacent, the Americans relied on their military superiority of their land power. 5,000 British soldiers were stationed in Canada. They faced 35,000 American soldiers with additional militia at their disposal. This should have made things clear, but the U.S. forces had too few professional officers. The troops were very poorly trained, and the militia proved to be more a burden than a help. Furthermore, many Indian tribes supported the British, for instance the Shawnee under their war chief Tecumseh.

In short, the American invasion of Canadian territory failed, no less than three times. In an 1814 retaliatory blow, the British even managed to burn the American capital Washington to the ground. The Capitol was destroyed, the White House damaged, and President Madison had to flee with his government.

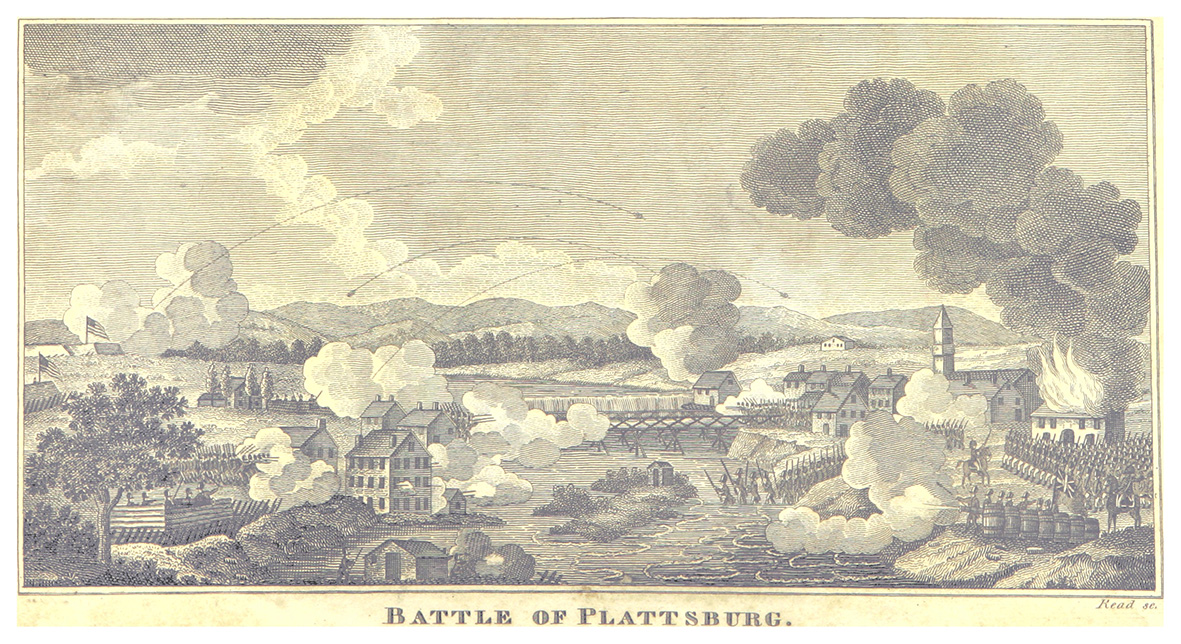

The Battle of Plattsburgh.

Things didn’t look so bright, therefore, which was exacerbated further when Napoleon resigned in 1814 and British forces were set free. Governor General George Prevost was sent to America with 11,000 men. He planned an offensive on New York, assisted by a fleet on Lake Champlain. This was where the city of Plattsburgh was located for whose defense Alexander Macomb was responsible. He had 1,500 men at his disposal. Militia in roughly the same amount was so poorly trained that their commander could only deploy them for fortification works.

Macomb acted cleverly and, through minor skirmishes and rapidly built fortifications stopped Prevost’s advance. Following the annihilation of the British fleet on the Lake as a consequence of Prevost’s indecisiveness, he ordered the retreat – against his officers’ wishes.

The Signing of the Treaty of Ghent. Oil painting by Amédée Forestier. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Treaty of Ghent

As early as the middle of 1814, when Washington was not yet destroyed and Plattsburgh not yet beaten, the two belligerents were more or less fed up with the war and met in the city of Ghent in Belgium, through negotiation of Russia. The British offensive having been failed may well have been an essential argument for enforcing the status quo before the war. On 24 December 1814, the peace treaty was signed.

The reasons for the war had become obsolete as well: The Continental Blockade had been lifted, forces recruitments were no longer necessary, and the war had weakened the Indian tribes to such an extent that it was their land that was then annexed and not Canada. The U.S. considered themselves victors in their Second War of Independence. And Alexander Macomb was their hero.

Berlin Auction 285, Lot 214: U.S. congressional gold medal for Alexander Macomb. Loubat, Medallic History USA nr. 45, pl. XLVI. Unique, awarded to the recipient by President Madison himself. Estimate: 150,000 euros

The fate of the hero

By resolution of 3 November 1814, he had received the gold medal from President Madison himself. He was one of only 27 men who were decorated this way, in recognition of their achievements in the Second War of Independence.

Manufactured by the die cutter Moritz Fürst, who was a Jew born in Preßburg, the medal’s obverse features the portrait of Alexander Macomb clad in his uniform, with his military title, while the reverse depicts the decisive naval battle and fighting land forces in the foreground.

The medal stems from the family possessions of the direct descendants of Macomb. Through marriage, Susan Watts Macomb (1849-1928), direct heir of the hero of Plattsburgh, the medal passed into the possession of the Grand d’Hauteville noble family.

And Alexander Macomb? On 29 May 1828, John Quincy Adams promoted him to the U.S. army’s Commanding General. In this capacity, he reformed the army. By increasing listed pay, he fought the frequently occurring desertions. He installed a relief system for widows and orphans of the officers who had died in battle. In addition, he established an officer retirement system to prevent over-ageing. He died on 25 June 1841 – not on the battleground, but sitting in his office – and was honored with a grave at Congressional Cemetery.

The medal offered by Künker is a high-class historical testimony recalling one of the pivotal moments in American history.

.jpg)