Reformation jubilees – A journey through the centuries

13. September 2017 12:50

If we are thinking of the early stages of the Reformation, then the lonely Luther springs to mind, nailing his theses to the door of the All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg. An image that is historically quite doubtful, for in the very extensive work of Luther there are exactly two passages that refer to these theses.

We know that he enclosed them to his letter of October 31, 1517, in which he asked Archbishop Albrecht of Magdeburg-Mainz to prevent the Dominican monk Johann Tetzel from selling letters of indulgence.

Luther also mentions them in a letter he wrote to a friend 10 years later, in which he reported that, during a small private celebration, he had toasted to 10 years of the ‘indulgences counterinsurgency’.

That this posting of theses is considered the beginning of the Reformation goes back to Philipp Melanchthon, who has generally shaped the theology and self-understanding of the Lutherans almost more than Luther himself. One year after Luther had died, Melanchthon wrote his life description. He writes: “Inspired by Tetzel’s selling of indulgences Luther issued theses on the indulgences and posted them on All Saints’ Church on October 31, 1517, for everybody to see.”

In 1617, the event celebrated its 100th anniversary. It was due to the (reformed) Palgrave of the Rhine and the (Protestant) Elector of Saxony competing over who was to lead the Protestant Estates, though, that this event became a jubilee.

By confessing to Luther, Friedrich V, the later Winter King, wanted to cover up the fact that the Reformed had not accepted the Confessio Augustana and consequently stayed absent from the Peace of Augsburg.

Johann Georg I of Saxony, in contrast, who had lost respect among the stern Protestants because of his support of the Catholic Emperor, stressed the traditional leadership role of Saxony as the ‘Motherland of the Reformation’.

The competition between the Reformed and the Protestant electors for the true succession of Luther ensured that the first 100th anniversary of the reformer posting his theses was solemnly celebrated in many places with a three-day festival from October 31 to November 2.

The celebrations proper were a balancing act, because the mood was tense. No Protestant wanted his celebration to provoke a war. And so they exercised restraint with regards to the sermons and ceremonies.

To the Protestant self-perception and the perception of others, the jubilee was nevertheless of the utmost importance. It was such a success, that the Catholics then borrowed the idea for themselves. In 1640, for instance, the Jesuits celebrated the 100th anniversary of their founding of the Order.

The year 1717 marked the 200th anniversary of the posting of the theses. The Saxons in particular had a problem with this celebration because Augustus the Strong had converted to the Catholic faith in 1697. Although prior to this, in the so-called ‘Religionsversicherungsdekret’ he had assured his subjects that they would be allowed to maintain their religious status quo, the festivities had to do without the Saxon Elector. Despite of this, Friedrich August commissioned his court medalist with producing official medals that praised not so much the Reformation but the Saxon Elector as its protector.

That was in line with the trend. We are now in the age of enlightenment. Religion and God were popular agents to call for a submission to the absolutistic ruler.

Also in 1717 the Protestant Estates didn’t want to provoke the Catholics with their celebrations. Or, as the Prorector of the University of Halle wrote to the responsible preachers, they decided to celebrate the festivities “without presentation, pomp, and art that enthralls the senses.”

By the time, the Pope had become politically so unimportant that he could be accused. And so numerous sermons revolved around Luther as the new Moses, who freed the pious from the yoke of the Pharaoh (= the Pope). Rome became the new Babylon and the Pope became the predecessor of the Antichrist.

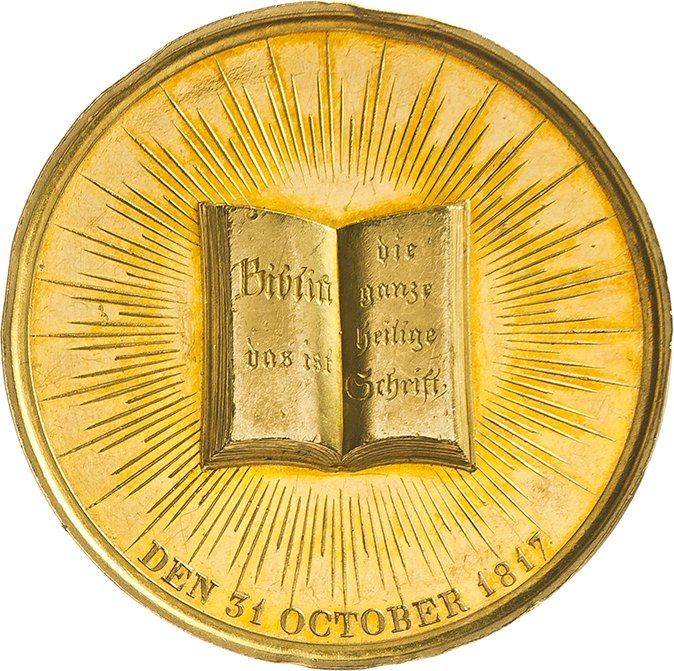

Celebrated on October 31, 1817, the 3rd anniversary of the Reformation had an entirely different background. The French army had just been expelled from Germany. The national movement monopolized Luther as a light-house German.

The prince of poets, Goethe, is a telling example. He suggested antedating the Reformation jubilee to October 18, 1817, so that it could be celebrated together with the 4th anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig. He considered the confessions a thing of the past, at any rate: “It (= Reformation jubilee) is celebrated by all believers and, in this regard, is more than a national festival: a feast of the purest humanity. No one asks the man of the landstorm about his confession, united they all proceed to the church, and are edified by the same service; all form a circle around the fire and are lit by one flame. All elevate their mind, commemorating that day, who owes his glory not just to Christians, but also to Jews, Mahometans, and Gentiles.”

Even when, as Goethe had demanded, 500 German-national students moved to the Wartburg on October 18, official Germany kept on celebrating the anniversary on October 31.

And everyone used Luther for his purposes: Friedrich William III of Brandenburg-Prussia announced the long-planned ecclesiastical union of Lutherans and Reformed (which Luther certainly would have supported). The traditionalists celebrated Luther as an important conservative who had preserved the Bible and its commandments. And the Pietists saw in Luther the great missionary who had embarked – just like them – to preach the gospel.

In 1817 the Reformation jubilee attracted international attention for the first time. It was celebrated especially by the many emigrated Protestants in the United States, who thus clang on to a piece of homeland and identity.

Luther Memorial in Worms, the largest Reformation memorial. Postcard from 1903.

1817 became the first of a variety of 19th century Reformation jubilees. Up until then the church and the state had assumed the leadership role but now it was civic festivals and associations that organized parades, collected money for statues, and decorated the city. Luther mutated into the quintessential German citizen and patriot.

In the early summer of 1914(!), shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, it was planned to mark the 400th Reformation anniversary with an international festival in Germany with representatives coming from the U.S., Canada, Australia, and the European nations.

This did not happen, though. During the First World War, there were other things to do.

Luther was exploited for German-national propaganda. For centuries, the historian Heinrich von Treitschke coined the image of Luther with his thesis that the reformer had anticipated German unification. He considered Bismarck the congenial successor of Luther. Only the German could understand Luther, because he embodied the innermost of the German people.

Of course Luther does not. The reformer was and still is a child of his time, whose ideas extended beyond his era. He is a projection surface for ideas that aim at gaining authority through his name.

The question remains whether in the 2017 Reformation jubilee we are coming the historical Luther anyway nearer or if, once again, we are using him as a protagonist for our own notions.