The Second-Heaviest Coin of Classical Numismatics

20. January 2023

About 15 kilograms, as much as 4 bricks or an about three-year-old child – that’s the weight of the second-heaviest coin of classical numismatics: a Swedish copper plate of 8 dalers issued in 1659. It comes from the Hagander Collection and will be sold by us on 2 February 2023 in Berlin as part of the Stefan Widegren Collection.

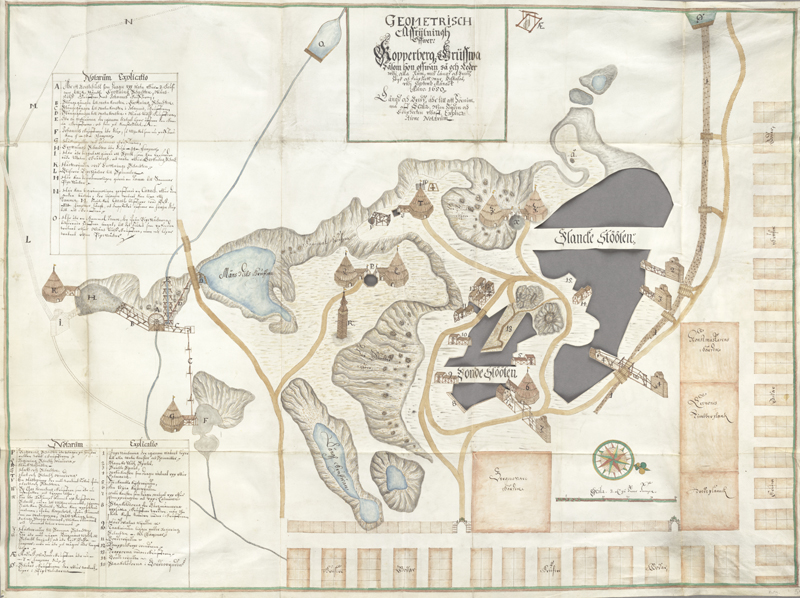

Plan of the copper mines of Falun. National Library of Sweden, inv. No. 10315723.

The Problem

In the 17th century, the most important copper mines of Europe were located in Sweden. The Falun Mine supplied two thirds of Europe’s demand for this wartime material. Copper was turned into bronze, which was then used to produce canons and muskets. Sweden’s rich copper deposits were a decisive factor in the country becoming Northern Europe’s major great power in the war-torn 17th century.

When it came to silver, however, Sweden barely had any deposits. But this metal was important, too – it was needed to pay mercenaries and for diplomatic purposes.

Therefore, already the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus wondered how to make as much silver as possible from Sweden’s copper reserves. Merchants in Amsterdam, where Sweden sold its copper, paid less the more metal the King had sent. His experts explained that the price would increase if the quantity supplied of copper decreased. Since Sweden dominated the market, it was easy to create an artificial shortage, they went on. However, this would naturally reduce the supply of silver in the short term, which meant that it would be impossible to keep up the supply of silver coins in Sweden.

The Solution

The easiest solution seemed to be obvious: why not use the copper that would otherwise be sent to Amsterdam as the basis for Sweden’s coinage? After all, this had already been commonplace regarding small denominations since ancient times. Thus, in 1624 a first run of copper coins with face values of 2, 1 and ½ øre respectively was issued. The weight of these pieces was devised in such a way that their metal value equaled their face value. As a result, the Swedish king had several options at his disposal. As long as the copper price in Amsterdam wasn’t to his liking, the coins would circulate in Sweden. If the price increased substantially, copper coins would be exchanged for silver coins and the copper would then be sold in Amsterdam.

The Outcome

By 1625, as much as 26% of Sweden’s annual copper yield was used for coin production. The Swedish government had vast quantities of these coins minted over the next few years. Unfortunately, this strategy was anything but successful. Enterprising Swedes came up with the idea of buying huge amounts of copper coins themselves and offering them on the metal market when the copper price increased. If, on the other hand, the silver price peaked, Swedes had to pay high fees to exchange the coins, which did not go down well with the population.

Riga had been part of Sweden since 1621. The ship that the copper plate offered by Künker came from sunk transporting Swedish currency to Riga.

A New Attempt

Since 1640, the royal council had discussed the introduction of copper plates as a means of payment for larger transactions. By now, Christina had succeeded her father as the monarch of Sweden, and Swedish troops were still fighting a seemingly never-ending religious war on German soil.

They were still short in silver and had vast quantities of copper. So why limit copper issues to øre coins? Why shouldn’t they mint copper dalers, too? Round patterns with a diameter of 22 cm and a weight of more than three kilograms were created with a face value of 1 ½ dalers. However, their production proved expensive, too expensive. Therefore, a member of the council came up with the idea of using the plates into which Falun copper had been processed for centuries to produce coins. This plate money could then be used both as ingots or coins, depending on the circumstances.

In 1644, this idea was put into practice. It was agreed that 10 dalers ought to equate 19.72 kilograms. We know from reports that the royal council considered this weight to be “bearable” – not only in a figurative sense. We know that 26,539 of these 10-daler plates were issued. Until 1974, not a single one of them was known of. The reason for the rarity of Swedish plate money is the fact that it was melted down as soon as the copper price rose above its face value – which occurred quite often. But in 1974, five specimens of this first issue were discovered in a ship wreck off the Baltic coast.

8-Daler Plate Money from the Hagander and Widegren Collections

Our example was also discovered in a ship wreck, which was found in the early 20th century at the entrance to the port of Riga. Most of the 8-daler plates it contained are now in museums, but Russian authorities sold very few pieces to private collectors.

Our plate was produced in 1659 under King Charles X Gustav. He had originally planned to sell the annual copper yield through a French syndicate. To speed up the negotiations, the King ordered in 1655 that no more copper plates be issued. However, the deal did not materialize, and the issuance of copper plates continued. Charles X Gustav did not want to deprive the treasury of this financial relief. After all, he was involved in several wars. In the year when our piece was minted, the Swedish army was fighting in Poland in the Little Northern War.

Plate money of 8 dalers has a weight of 14.6 kilograms – the coinage ordinance of 1649 stipulated a weight of 1.812 kg for every daler. The size is remarkable too: 34 x 62.5 cm. At the center the face value was added by means of a circular die, in the corners we can see the marks of circular dies with a crown and the year.

The End of Plate Money

As early as in 1646, a halt was put to the production of 10-daler plates, in 1682 the production of 8-daler plates was stopped, too. However, smaller copper plates were still issued in the 18th century. It was not until 1 January 1777 that copper plates were taken out of circulation. By then, more than 44,000 tons of Swedish copper had been minted into plate money.