The royal wedding of Kulmbach

14. September 2015 15:14

To regard coins of the early modern period merely as currency completely overlooks an important fact: their role as courtly representations of the renaissance ruler.

This is just one of many gems of the biggest collection of coins and medals from

Brandenburg-Franconia ever to be on the market: a rare 1579 gold gulden, which

played an important role at the royal wedding at Kulmbach.

As an example, let us take a look at a gold gulden struck in 1579, which, at first glance, does not seem different than others. The obverse depicts George Frederick in full armor. As referred to in the inscription and shown through the coat of arms, he was not only Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, but also Duke of Prussia. The coat of arms shows the Prussian eagle, the Pomeranian griffin, the lion symbolizing the title of Burgrave of Nuremberg, as well as the quartered coat of arms of the Hohenzollern in silver and black. And lastly, the heart-shaped shield depicts the Brandenburg eagle.

Inner courtyard of the Plassenburg castle. Photo: Wikipedia / Guido Radig. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

But because of archival records the real purpose of this inconspicuous gold gulden can be revealed: It served as prize money for one of the most lavish festivities ever held at Plassenburg castle, which, at that time, had just been rebuilt.

The setting of the festivity was Georg Frederick’s second marriage. He had lost his first wife, Elisabeth von Brandenburg-Küstrin, and through his proclamation as Duke of Prussia by the Polish King, his search for a suitable spouse vastly widened. He decided to court and marry Sophie von Braunschweig-Lüneburg, the eldest daughter of the powerful Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, George Frederick turned his wedding into an event, which documented his status elevation and it became the top subject of conversation for miles around.

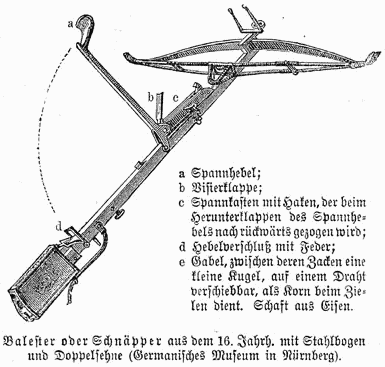

But to achieve such an impact he first had to attract as many people from all strata of society to come and join him at the festivities at Plassenburg. He did so by calling a shooting competition named “Stahlschießen” or “steel shooting”. According to an 18th century encyclopedia it is defined as follows: “Steel shooting: in some villages the festive shooting on a target with a crossbow. The term derives from the crossbow’s steel bow, as well as from the steel bow used for shooting.”

Crossbow of the 16th century with a steel bow and double bowstring. Source: Wikicommons.

In this context it is important to know that in the 16th century cross bow shooting was a favorite sport of the aristocracy and upper class. At the time of Georg Frederick three official cross bow shooting societies could be found in Nuremberg alone. These shooting societies can be compared to modern sport clubs and so the practice of the cross bow did have a priority, next to the social role. Especially Nuremberg was famous for its shooters and it therefore comes to no surprise that 28 of the 152 attendees came from this city.

Two "Pritschenmeister" in a manuscript, Worms 1575. Source: Wikicommons.

One of the essential elements of the competition as a whole was the so-called “Pritschenmeister”. He had the dual role of referee and master of ceremonies - and wearing a jester’s costume, he also provided entertainment. The best “Pritschenmeister” were famous even far beyond their home town, which is why Georg Frederick asked the attendees of the city of Esslingen to bring their “Pritschenmeister.”

The entry fee for the competition for every shooter was 4 thalers and the prize money amounted to an impressive sum of 100 ducats. It could have been paid out in gold gulden, such as our specimen, just as they certainly were used for the smaller prizes: every shooter, who hit the bull’s eye, was awarded a gold gulden attached to a silk banner and a plate made of pewter carrying a glass of wine and bitter orange. But also the misfortunate shooter received a “prize”: a linen flag and a plate made of wood carrying a glass of beer and bread with farmers cheese on the side.

With 16 hits, the winner of the competition was August, the Elector of Saxony. But next to members of the high society, also “ordinary”, non-noble, people were allowed to participate. It is said, that Georg Frederick granted the illustrious men a small advantage by moving the shooting stand closer by nearly 20 steps. If this was known to the shooter beforehand and he could even practice at this distance, he could easily have gained a head start. Over the course of the competition, which lasted 4 days, a total of 24 shots were fired – which left the attendees plenty of time to enjoy all the other entertainments.

August von Sachsen, by Lucas Cranach the Younger, around 1572. Source: Wikicommons.

For the opulent banquets a new cooking rage for pastries had been installed at Plassenburg, next to rebuilding the entire kitchen. Furthermore the noble and the common guests were entertained by exhibition fights and a grand display of fireworks.

Margrave George Frederick, by Lucas Cranach the Younger. Source: Wikicommons.

George Frederick’s plan succeeded: His elaborate and generous celebration of his wedding to Sophia Braunschweig-Lüneburg demonstrated his new status as Duke of Prussia to his subjects and his fellow noblemen alike. The gold gulden, which accompanied prizes awarded to the attendees, bears witness to this spectacle of a renaissance ruler. Many of the gold gulden that were taken home probably never saw any circulation, since they most likely became part of their owners coin collection. Nowadays though, there is only one such gold gulden known to be in private possession and this very specimen will go under the hammer at Künker Auction 267. The Auction will take place on September 29th of this year and the pre-sale estimate of the specimen is 20,000 euros.

The Roland Grüber Collection will be on sale at Künker Auction 267

on September 29th and 30th, 2015.