Two Cityscapes on Coins from Frankfurt am Main and the Artwork that inspired them

08. September 2023

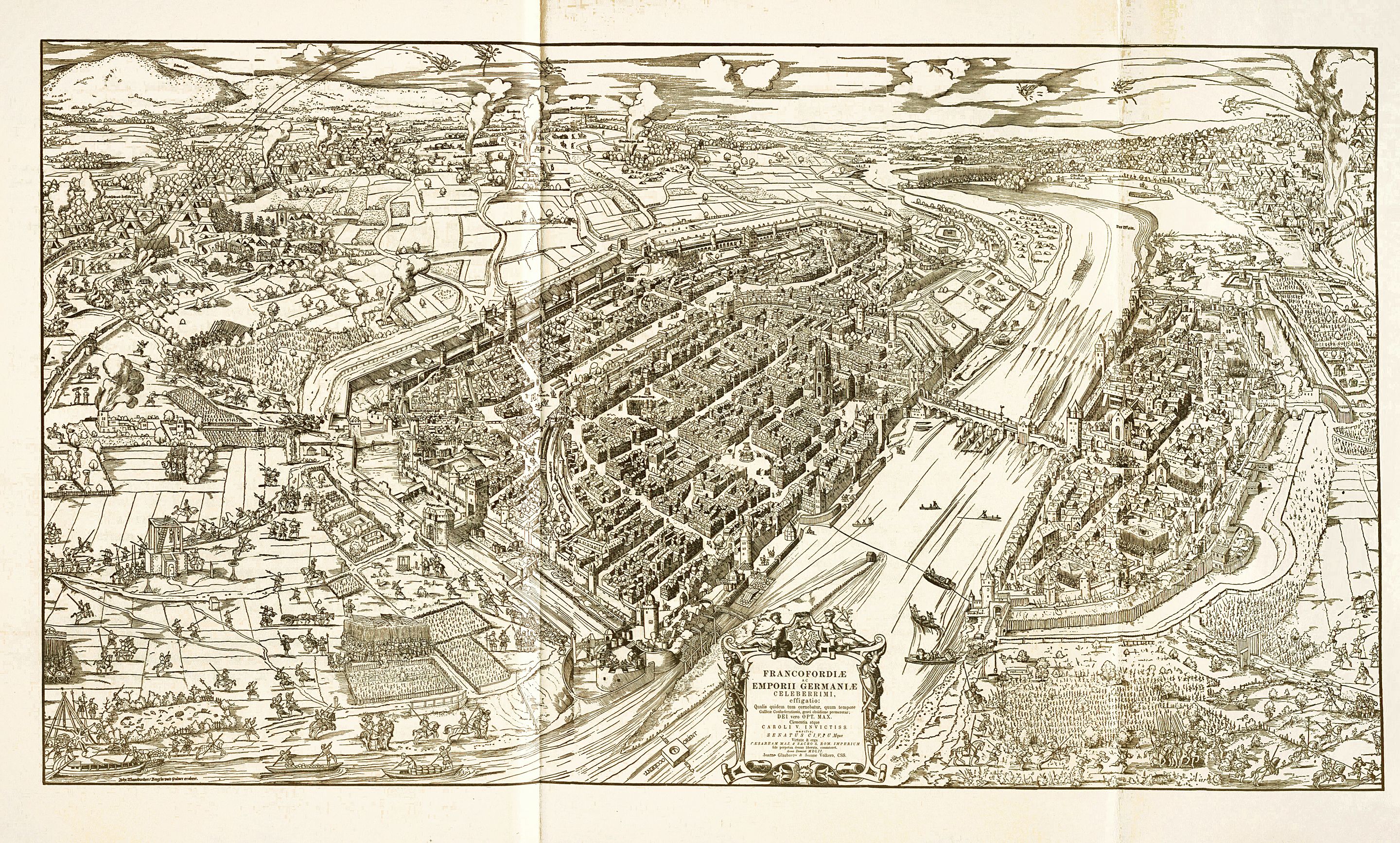

Siege plan of the city of Frankfurt based on the original by Conrad Faber von Creuznach, 1552.

The City Wall of Frankfurt in 1552

Let us take a look at the first known city plan of Frankfurt. It was produced in 1552 during the unsuccessful attempt by Maurice of Saxony to besiege the city – which was loyal to the emperor – and shows us what the city’s fortifications looked like at that time. Large parts of these fortifications still dated back to the Middle Ages and were therefore completely outdated. Despite this, the people of Frankfurt were able to fend off their attackers because the city had strong artillery at its disposal.

At the start of the Thirty Years’ War, the situation was different. The military had become more professional. A citizens’ militia was no longer capable of standing up to an experienced army of mercenaries. On top of that, the walls were still the same as they had been in 1552. A few shots from a modern canon would be enough to bring them crashing down.

Some of the city fathers must have felt uncomfortable about this, but no one dared to ask the citizens to bear the costs of rebuilding the fortifications. In 1618, an Electoral Palatine engineer estimated the construction costs at 149,000 gulden.

Gold gulden from 1619 to mark the election of Ferdinand II as Holy Roman Emperor. Rare. About extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker auction 392 (2023), No. 2242.

Construction Plans For A New City Wall in Frankfurt

This amount was not calculated in coins, of course, but in “guldens of account”, a currency used purely for calculation, which – depending on gold and silver prices – usually equated to a higher amount when indicated in real gold gulden, and sometimes a lower one. The city council rejected this first cost estimate, but demanded another just two years later. This time, the engineer estimated the cost at 159,600 guldens of account. This estimate was also rejected by the city fathers at their meeting of 10 May 1621, because they believed the war would probably be over soon.

However, this was a miscalculation on the part of the city’s politicians. The war did not end, but drew closer. On 20 June 1622, a battle was fought near Höchst, about two hours’ walk from Frankfurt. Then, finally, the decision was made to start constructing the fortifications. But oh, the expense! The first fortress architect gave up because the city council did not provide him with enough money. The second attempted to realize a more economical version. But the collapse of a bastion led him to realize that he had overestimated his abilities, as well as the public’s willingness to make serious sacrifices.

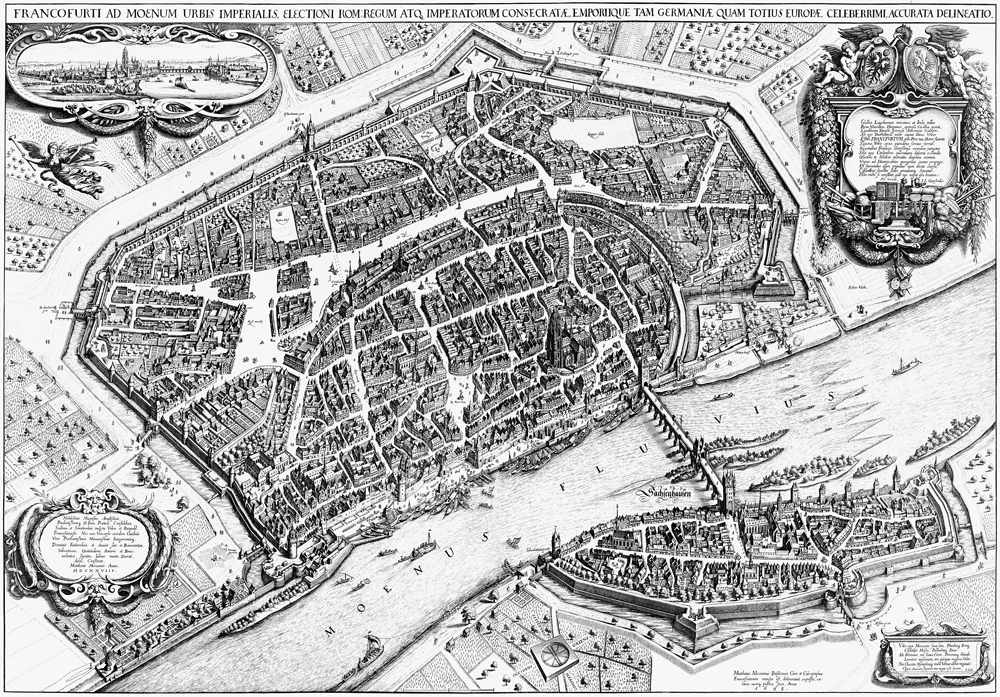

And so, on 8 January 1628, Wilhelm Dilich and his son Johannes Wilhelm came to Frankfurt. A copper engraving by the great Matthäus Merian shows us what the city wall looked like when they arrived.

Copper engraving by Matthäus Merian, dated 1628.

It could certainly be the case that this copper engraving was influenced by Wilhelm Dilich’s drawings of Frankfurt. Dilich drew the city as a basis for the design of the new fortifications. Over the following decades, Frankfurt’s walls were constructed according to his plans.

Merian, who lived in Frankfurt, will have known and used these plans. After all, it was common for engravers, as well as die cutters, to draw on existing models for their own work.

In the vignette in the upper left corner, Merian actually quotes himself.

Detail from a copper engraving by Matthäus Merian, dated 1628.

Copper engraving by Matthäus Merian, 1618.

It is a much smaller and simplified version of an older copper engraving from 1618. And now, pay close attention to the ship in the middle of the Main.

Detail from the copper engraving by Matthäus Merian, dated 1618.

Frankfurt. Half reichstaler 1648. Cityscape as seen from the south. Very rare. From Adolph Hess auction 253 (1983), No. 419. Wonderful toning, extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros. From Loos Collection, Künker auction 392 (2023), No. 2289.

The City Wall During The Thirty Years’ War

If we choose a corresponding detail from the 1618 engraving, we can see right away that this image inspired the design for this 1648 half reichstaler. But with one key exception: the rural landscape surrounding the city, with its mills and gardens, is gone, replaced by the bastions built during the Thirty Years’ War according to Dilich’s plans.

This major project was officially launched on 16 June 1628, with up to 600 men working on it at the same time. Of course, these people were not all experienced fortress builders, of whom there were relatively few. Conscripted citizens were obliged to carry out manual work. Even the teachers at the city’s grammar school had to help out alongside their lessons – which they protested strongly against, by the way. But it was no use. They continued to march to the construction site like everyone else, behind beating drums and a waving flag. Only the wealthier citizens could afford to send a farmhand or maid in their place.

This drawing by Dilich, which was enhanced in the 19th century using Merian’s plans, shows us what the new bastions looked like.

The bastions of Almeida, Portugal, were built around the same time as the ramparts of Frankfurt. They provide a good idea of what the ratio of earth to walls may have been like in Frankfurt as well. Photo: KW.

Nowadays, untrained workers on a building site would be more likely to hold things up. But back then, construction projects required droves of laborer to carry out the extensive earthworks. For example, the old city moats in front of the wall had to be filled in, and the bastions had to be raised. Huge earth walls were built to absorb the impact of cannon fire, which were only covered at the outside by stone walls. In front of these walls, moats were dug. These prevented enemy sappers from tunnelling under the earth walls and detonating underground mines there, which would have caused part of the fortifications to collapse.

At the end of 1631, when Gustav Adolf of Sweden demanded entry at the gates of Frankfurt, these fortifications had not yet been developed to the point where the city could dare to resist. Frankfurt’s city fathers had no choice but to put aside their loyalty to the emperor and welcome their fellow Protestant into their walls. Frankfurt was spared, in exchange for considerable tributes.

We know the figures from the accounting year 1633: in this one year, Frankfurt paid 168,038 gulden of account to the Swedes as a tribute. The city also had to pay 61,922 gulden for wages and 44,939 gulden for the construction of the fortifications. (These figures are taken from Friedrich Bothe, “Gustav Adolfs und seines Kanzlers wirtschaftspolitische Absichten auf Deutschland” (English: Gustav Adolf’s and his Chancellor’s Economic Intentions for Germany). Frankfurt (1910), p. 209ff.)

The Swedes insisted on completing the fortifications under immense pressure. They hoped to have a fortress in Frankfurt for their own purposes. But when the army had to withdraw in 1635, the circle of walls had not yet been completed – and it would not be until long after the end of the Thirty Years’ War. The fortress was not completed until 1667, and even after that, the city had to invest several thousands – often several tens of thousands – of gulden in its maintenance every year.

Frankfurt. Reichstaler 1696 (year changed from 1695 on the die). Very rare. About extremely fine. Estimate: 3,000 euros. From Loos Collection, Künker auction 392 (2023), No. 2299.

Frankfurt Port

Frankfurt could afford it, as this coin design seems to illustrate:

Detail from Künker 392 (2023), No. 2299

Trade is booming. There are numerous ships moored at the landing stage being loaded and unloaded with the port crane. On the wharf, we see dockers transporting the goods to their respective warehouses. But be careful! Once again, this image is not a contemporary design created by the coin engraver in 1696.

View of the port of Frankfurt by Matthäus Merian, 1646.

In fact, it was produced half a century earlier, during the Thirty Years’ War in 1646. Matthäus Merian designed this copper engraving with a view of Frankfurt port. Again, this is clearly indicated by the ships.

Detail from Künker 392 (2023), No. 2299

Detail of the port view by Merian, 1646

There are several ships are arranged around the breakwater: on the right, we see the largest, which has a clearly identifiable rigging without hoisted sails; directly in front of the breakwater, we see another ship with rigging; to the left of the breakwater, by the wharf, lie more ships whose rudders are clearly highlighted. The only thing to have changed is the small rowing boat to the left of the breakwater, which becomes a sailing boat in the coin design.

So, when we admire the cityscapes depicted on coins, we should always keep in mind that they were probably not designed by the coin engravers themselves, but rather based on a copper engraving. Perhaps it was contemporary, perhaps it was made much earlier.

Incidentally, this applies not only to cityscapes, but also to many historical medals. Identifying the models is a difficult and time-consuming task, but one that has been made much easier by the use of the Internet. Why not try it out for yourself and search for the models that inspired your own coins?