Bulgaria, Prince Ferdinand I and the Railway

08. November 2023 15:41

We can appreciate the historical background against which the medal offered in our forthcoming Auction 395 was created only if we remember that the Bulgarian government planned to bring the territory, long neglected by the Ottoman Empire’s central government, closer to Western and Central Europe. Bulgaria was to become an economically strong nation in order to secure its independence. And in all of these considerations, two issues were decisive:

- How would Bulgaria succeed in gaining investors’ confidence?

- And how, with the help of investors’ money, could the infrastructural backlogs be made up as quickly as possible?

The Prince: A Glorified Symbol of the Bulgarian Nation

We should keep in mind that the time of absolute monarchs was already long gone. The young nation of Bulgaria had given itself an extremely liberal constitution, and to this end sought a sovereign who would himself exert as little influence as possible on the government. At the same time, he was to be well enough anchored among the European high nobility and the Western economic elite to raise state bonds for Bulgaria. Moreover, a potential candidate had to appeal to all the great powers of Europe. He had the task of maintaining a balance between France and Russia on the one hand, and the German and Habsburg Empires on the other. Each of them had its own agenda in the Balkans, as did Britain.

Alexander I of Battenberg had failed in this task. After his resignation, the Bulgarians gave the office to Ferdinand I of Saxe-Coburg-Kohary in 1887. Ferdinand was the youngest son of an Austrian general from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and, through his father, was related by blood or marriage to almost all European ruling houses. His mother Clémentine of Orléans was the daughter of the French bourgeois king Louis Philippe, and brought to the equation not only great personal wealth, but also excellent connections to the French business world.

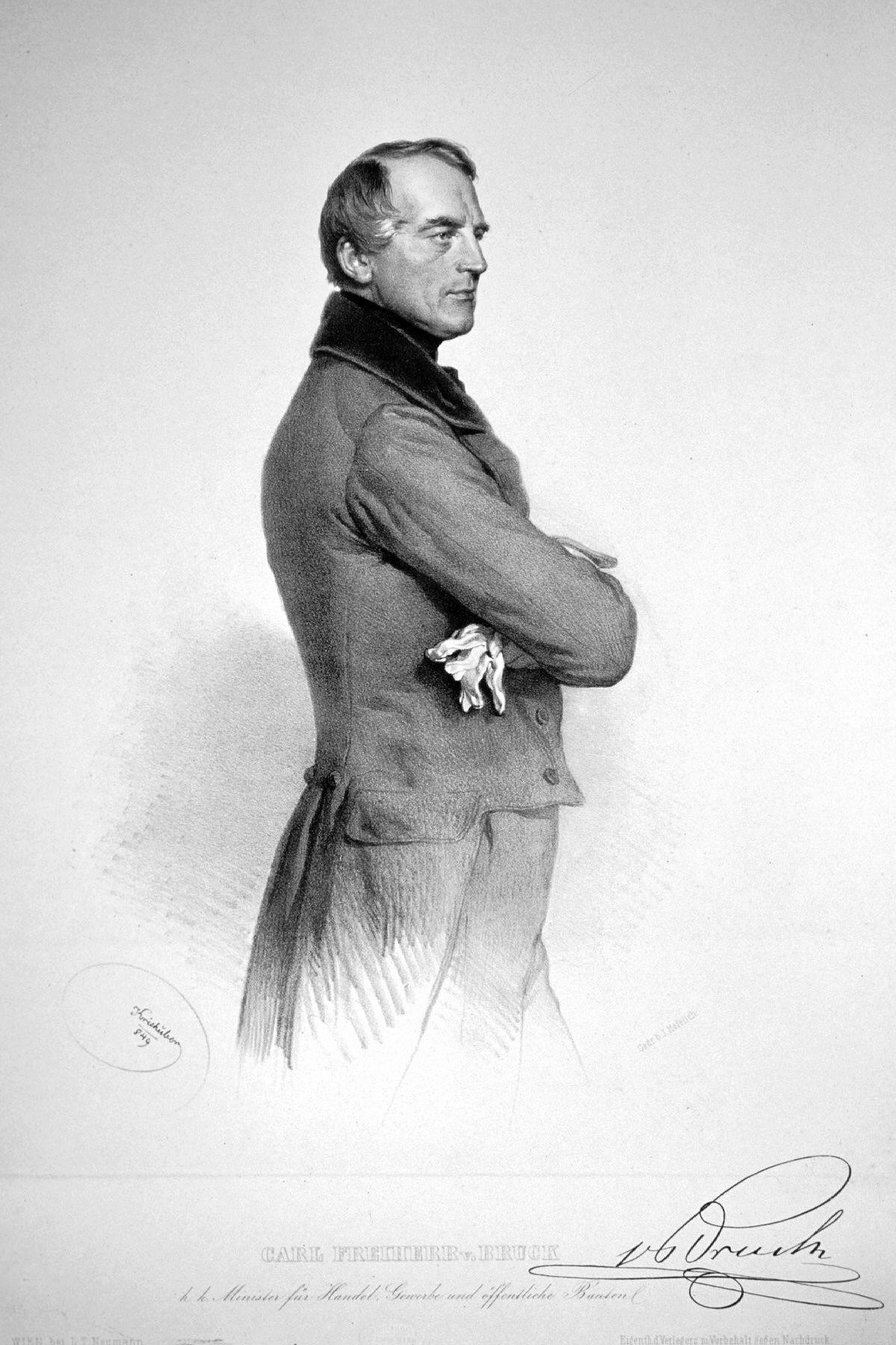

Portrait of the youthful ruler upon taking office

During the first years of his reign, Ferdinand I travelled repeatedly to the rich industrialised countries of Europe to promote Bulgaria’s cause. In doing so, he gained entry to the salons of the moneyed aristocracy in a most imaginative way. A good example of this is the manner in which Ferdinand managed to establish personal contact with Friedrich Alfred Krupp in 1893. Krupp manufactured weapons, locomotives and railway carriages, and all were of great interest to a country that was investing in its infrastructure while building a modern military. In order to get an invitation from Herr Krupp, Ferdinand sent him one of the most important Bulgarian medals of honour. Naturally, he received a letter of thanks combined with an invitation to the Villa Hügel, which Ferdinand was only too happy to accept. He travelled there and brought the future Bulgarian Prime Minister with him, for a quiet and serious business discussion.

Whenever it became difficult to obtain loans, Ferdinand personally intervened in negotiations. He was supported by Georg von Siemens -- one of the founding directors of the Deutsche Bank, which was particularly committed to investing in railway projects. It financed not only the Baghdad Railway, but also the Northern Pacific Railway and the Yambol-Burgas line in Bulgaria, upon completion of which this medal had been minted.

Incidentally, Ferdinand I was also remunerated for his services. He received 300,000 francs a year, and an additional 90,000 francs from Eastern Rumelia. This was more or less the sum the kings of Serbia and Greece collected for their services. After his marriage (and presumably also because it had become apparent how successful he was in attracting investors’ money abroad), the Bulgarian government increased his salary to 1.3 million francs annually.

Industrialisation and Railways

Under the Ottomans, Bulgaria had been an agricultural nation whose well-being depended on the weather. If there was a bad harvest, the state budget process immediately became difficult. Thus, after the two bad harvests of 1898/9, the government was forced to immediately reduce the salaries of ministry officials by 15 to 30%. To forestall resistance, Ferdinand at the same time voluntarily dismissed 50% of his civil list.

In such a tight financial situation, the government had no choice but to pay for the construction of the infrastructure through government bonds. The railway was the top priority, since it was of existential importance for transporting goods to and from Bulgaria.

One detail illustrates how quickly and effectively the railway was built: When Ferdinand I travelled to Bulgaria in 1887 to be crowned in Sofia, he did so by coach, ship and horse, constantly in danger of being attacked by highwaymen. By the time his young wife arrived in Sofia in 1893, she was already taking the train.

One can also express this tremendous achievement in figures: When Ferdinand took office, the Bulgarian railway network covered 541.5 kilometres. When he stepped down, 1,683 kilometres of new railway had been built. With Ferdinand’s help, the Bulgarian government borrowed 328.6 million leva in government bonds for this purpose. The Bulgarian railway network with all of its facilities served as collateral for the investors.

The Orient Express

The money would never have been raised without Ferdinand’s commitment. This became evident when it came to building the last section of the legendary Orient Express. On 1 November 1887, the Serbs had completed their section of the line. Now the route from Western Europe to Istanbul was interrupted only in Bulgaria.

The problem: When Ferdinand took office, Bulgaria was not considered a good credit risk. European financiers were reluctant to invest in a project they did not believe would be completed in any acceptable period of time. And this is where Ferdinand’s mother stepped in: She made one million francs available as a loan from her private fortune. Naturally, the entire business world then looked with great interest to Bulgaria, to see whether the state could repay its debts.

It did. The railway line was built in record time. On 19 June 1888, on the occasion of Ferdinand’s first Throne Jubilee, he was able to open the line internally. On 9 July of the same year, a train from the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits ran on the new line to test it. And beginning on 12 August 1888, the Orient Express ran continuously between Paris and Istanbul. The Bulgarian State Railways received its share of ticket sales money and was able to repay the loan including the high interest rates.

This broke the ice, and when Bulgaria issued a large government bond in 1889, it was oversubscribed sixfold. Bulgaria offered the highest interest rates in Europe at the time.

The railway line from Yambol to Burgas

The railway line from Yambol to Burgas was not yet financed with this capital, but that too was accomplished, with the help of the Deutsche Bank in cooperation with the Wiener Bankverein. The law authorising the construction of this railway line was passed on 21 January 1889. The line was to connect fertile western Bulgaria with the important Black Sea port of Burgas. Bulgaria hoped that this stretch of railway would provide better access to the European market for its grain.

Ferdinand I travels to Russia in 1902 in his personal salon carriage. Bulgarian State Archives 3K / / 476 / 16.

The first sod was turned on 1 May 1889. The 110 km-long railway line was built in a record construction time of just over a year by Bulgarian “Pioneer and Engineer Troops”, and with the help of labour from the local population. Thus it could be ceremonially opened on 14 May 1890.

Advertising poster for the Orient Express, 1888.

The Bulgarian government’s calculation was successful. Only a few years later it became clear that the port of Burgas would have to be expanded in order to ship even more tobacco and grain across the Black Sea. In 1898, the Bulgarian People’s Assembly decided to expand the port at a cost of 20 million leva.

A medal “For the construction of the railway line from Yambol to Burgas”.

To return to the railway line from Yambol to Burgas: On the occasion of its completion, the Bulgarian Ministry of Finance, by Ukas No. 76 of 14 May 1890 (published in the State Gazette [Държавен вестник] No. 110 of 25 May 1890) created the medal “For the construction of the railway line from Yambol to Burgas” [Медал “За Построяване Железопътната Линия Ямбол – Бургас”].

The medal exists in three sizes: diameter 90 mm, non-wearable, in gold; diameter 50 mm, non-wearable, in bronze gilt, in silver and in bronze; and diameter 30 mm, wearable, in silver and in bronze. The designs were by Joseph Christian Christlbauer (1827-1897); the dies were cut by Johann Schwerdtner in Vienna, where the minting was also done.

According to Pavlov (in PA p. 248) and Petrov (in PE5 p. 176 f.), only one medal with a diameter of 90 (de facto 89.6) mm was initially minted, probably in 986/000 gold to 110 ducats, with a total weight of 383.2 g, and was awarded to Prince Ferdinand I in a bordeaux-coloured octagonal velvet case. On the obverse is the portrait of Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria facing right, with the circumscription ФЕРДИНАНД IИЙ КНЯЗЬ НА БЪЛГАРЯ [Ferdinand I Prince of Bulgaria], below the neck section the die-cutter’s signature “J. SCHWERDTNER”, and on the reverse a steam locomotive crossing a bridge -- probably over the river Tundscha [Тунджа] near Yambol, with the circumscription ЯМБОЛЪ - БУРГАСЪ * 14 МАЙ 1890 * [Yambol-Burgas * 14 Мai 1890 *]. The design of the steam locomotive was likely modelled on the type of which an example, No. 148, is exhibited today in the Bulgarian Railway Museum in Russe [Русе], northern Bulgaria.

After the death of Ferdinand I on 10 September 1948, the medal passed by inheritance to his youngest daughter Nadejda, Princess of Bulgaria (30 January 1899 - 15 February 1958), who was married to Albrecht Eugen Duke of Württemberg (8 January 1895 - 24 June 1954), and after her death it went to her heirs.

According to Pavlov (in PA p. 248) and Petrov (in PE5 p. 176 f.), a second “Great Gold Medal”, identical in diameter, was given to Prince Ferdinand’s mother Clementine at his request, as a token of appreciation for her great idealistic and material support in the development of the Bulgarian railway. However, this medal is considered lost.

Künker is proud to be able to offer this great rarity in its Auction 395. The piece offers testimony to the personal commitment and enthusiasm with which Ferdinand I championed the development of his country by means of the railway.

The Railway Tsar

This enthusiasm, which seems slightly out of place in a ruler, is responsible for the many anecdotes that circulate about Ferdinand I and his love of locomotives. The accuracy of these stories cannot be vouched for, but some of them are too good not to be told.

In any case, we can believe that the intelligent and technology-loving prince knew a lot about the subject. He probably personally decided which type of locomotive to buy when his mother donated the traction engines for the railway line between Vakarel and Zaribrod.

Ferdinand almost always visited factories during his travels, and is said to have amazed the local technicians with his extensive knowledge. Of course, Ferdinand often travelled by train, but he is also said to have been able to drive a steam locomotive himself, which was not a widespread skill in the 19th century – especially among members of the “better” classes.

Was Ferdinand really able to drive trains? What is remarkable above all is that he was believed to be capable of it. A prince who was prepared to get his hands dirty: What better image could a constitutional monarch spread of himself to convince his subjects that he was committed to Bulgaria? So perhaps there is something to it when you read that Ferdinand I loved to tease the reception committees at the railway stations. They gathered, of course, where his private parlour car was scheduled to stop. But instead of waving courteously from the saloon car, as expected, the Prince is said to have jumped off the locomotive in his railway smock, his face smeared with soot and his hands dirty.

Caricature from 1908 playing on Ferdinand’s enthusiasm for railways: Ferdinand enthroned on a locomotive. It is pulled by the Prime Minister, who leads Ferdinand by the nose. Ivan Geshov, another Bulgarian politician, pushes from behind while the Berlin Treaty personified goes under the wheels. In the background, exuberant Bulgarians cheer this trip to Constantinople. The cartoon refers to the fact that Bulgaria asserted its independence in 1908 and elevated Ferdinand I to Tsar.

The Western media, of course, made fun of this. It was said that Ferdinand I, travelling on the Orient Express, had asked the driver to let him take the controls. He had supposedly indulged in the fun of driving fast and then braking sharply. The passengers were said to have complained about this to the railway authorities, whereby the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits instructed its staff not to let the prince into the locomotive any more.

There may have been a healthy dose of envy in all of these jokes, directed at a prince who, in collaboration with the economic elite of Europe, put a country “at the (then) end of the world” on the map in just a few years. Otto von Bismarck, at any rate, held Ferdinand in high esteem: “Prince Ferdinand is undoubtedly more capable than his reputation in the satirical magazines suggests, and more capable than most other princes.”

This opinion was probably shared by the Bulgarian locomotive drivers. A delegation is said to have awarded Ferdinand I the locomotive driver’s “diploma Honoris Causae”, so to speak. It is also said that Ferdinand did not miss the opportunity to thank the train crews personally at the end of a train journey, and to hand out bonuses and cigars.

Rising exports and flourishing trade

True or not: It’s difficult to judge. What is certain, however, is that the railways brought an enormous boost to Bulgaria’s development. On the Orient Express line, machinery purchased in Western and Central Europe came into the country -- duty-free and at reduced freight rates.

Conversely, the Yambol-Burgas railway line brought the crops of western Bulgaria to the Black Sea, whence they were shipped to Europe. The export of grain and grain products to Germany increased from a volume of 7,900 leva in 1891 to 11,380,000 leva in 1912.

The “Prussians of the Balkans”

Ferdinand I also succeeded in improving Bulgaria’s image in Western Europe. Otto von Bismarck liked to call the Bulgarians the “Prussians of the Balkans”, and for him this was high praise. And as early as 1890, he paid the Bulgarian nation a great compliment: “From all that can be seen and observed among the Balkan states, the Bulgarians seem to me to harbour a talent for state-building and state-maintenance. And they are an efficient, industrious and thrifty people, who pay homage to slow, deliberate progress. It honours, improves and strengthens them, and that pleases me ...”

The gold medal of the railway line from Yambol to Burgas held by Ferdinand I is a wonderful reminder of a great ruler, and of a people who managed to become an important part of Europe in just a few decades.

Ursula Kampmann, Michael Autengruber