Gold from Rhodes for the Battle for Rome

07. October 2024 10:53

It always seems so simple: a knife, a bullet, a bit of poison and the tyrant is gone and freedom restored. But the men who successfully assassinated Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BC found out that, unfortunately, the world does not work this way. Although Caesar fell to their daggers, nothing that happened afterwards went as planned: no one was interested in Brutus’ eloquent appeal to restore the Republic as his audience had fled to safety.

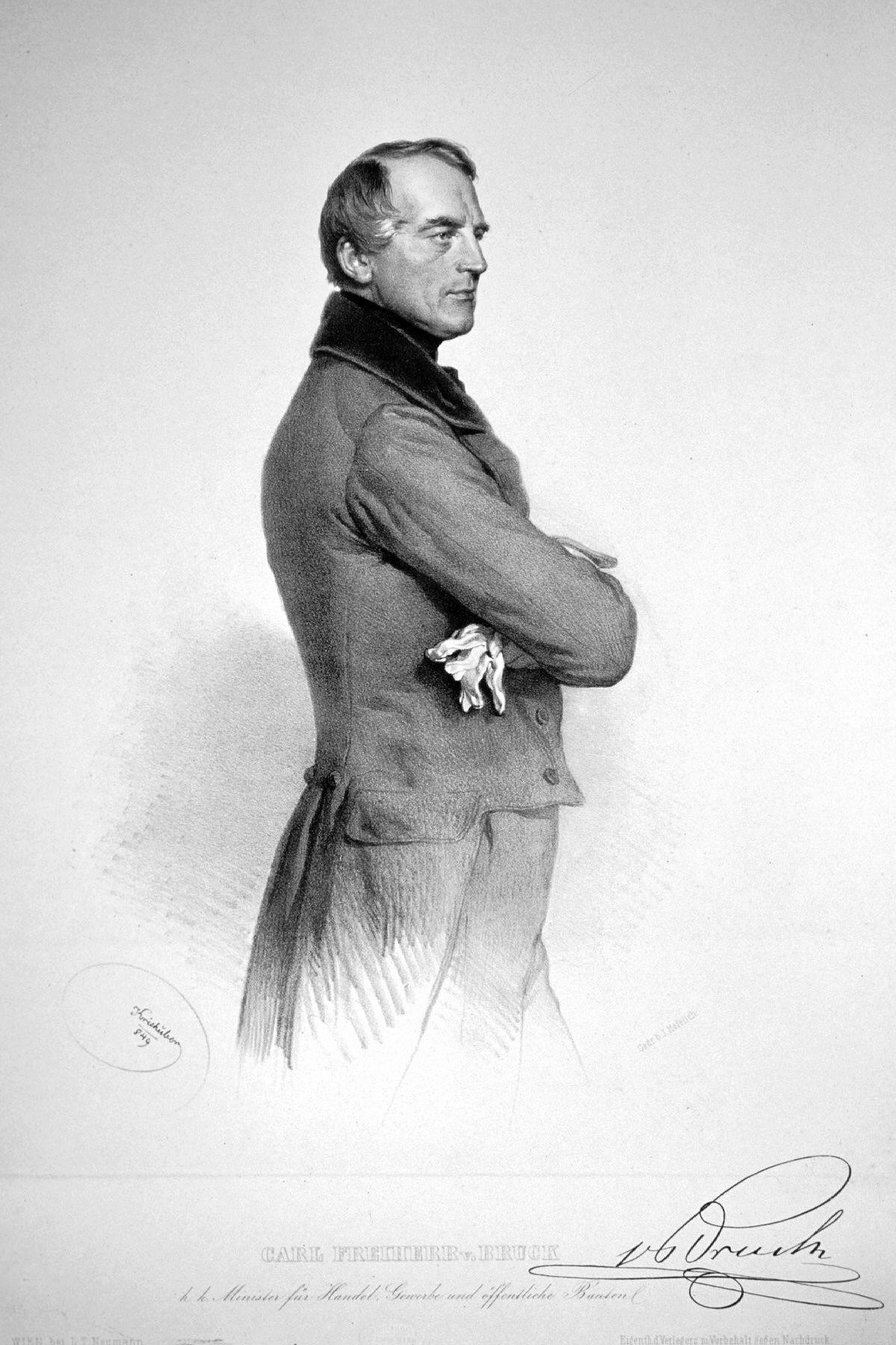

Portrait of Brutus. Glyptothek Munich. Photo: KW

Brutus and Cassius Driven Out of Rome

What was to happen after the assassination? Nobody knew. So they decided to do nothing for the time being. On 17 March 44 BC, the survivors agreed not to change Caesar’s decrees, while his assassins were granted amnesty. This was a declaration of political ruin for both sides. Brutus and Cassius did not reap the fruits of their conspiracy, and Mark Antony refrained from taking revenge.

Of course, this agreement was not permanent. It was only a means to buy time for the battle lines to be drawn. In this process, Mark Antony discovered what a good hand fade had dealt him. He was a consul, while his opponents Cassius and Brutus were only praetors. This opened up a number of possibilities for him.

At the beginning of June, Mark Antony succeeded in persuading the Senate to assign his opponents the task of procuring grain in the provinces of Asia and Sicily respectively. An affront! A praetor’s place was in Rome. This mission was nothing more than a nicely disguised way of taking away their praetorships. It was a declaration of war, and it was understood as such. The next coup followed a few days later. Mark Antony had the Senate vote on which provinces Cassius and Brutus were to administer once they had completed their terms as praetors. They were given Crete and Cyrene respectively – the least important provinces in the entire Roman Republic! But what could they to do? Assassinate Mark Antony, too? By then, they deeply regretted not having done so on the Ides of March. But public sentiment had turned. Brutus and Cassius no longer dared to enter Rome. They left Italy in early August and immediately began to gather supporters, collect resources and recruit soldiers in the eastern provinces. The official legal break came on 28 November 44 BC, when Mark Antony gave the provinces that had been allocated to Brutus and Cassius to someone else.

The Acropolis of ancient Rhodes. Photo: Ymakris, cc-by 4.0

The Subjugation of Rhodes

Early in 42 BC, the two met in Smyrna to discuss the next steps. It was decided not to wage war against Mark Antony immediately, but to first defeat the only two powers in the east that had not yet surrendered. Rhodes and the Lycian League refused to finance the Roman civil war with their wealth. A terrible mistake. Brutus marched against the Lycians, and Cassius against Rhodes.

Appian tells us in detail how the two military commanders proceeded. At this point, we are only interested in the subjugation of Rhodes. Cassius’ troops were far superior to the naval force. First he defeated the Rhodian fleet in two naval battles, then he surrounded the city from both sea and land. When the Rhodians realized their defeat was inevitable, they opened the gates and surrendered, for better or worse. In this way, they probably saved their lives and their freedom. However, Cassius confiscated all their possessions, and not just the treasures found in the temples and public coffers. He demanded that all citizens surrender their private savings or be put to death. The Rhodians probably smiled at that, as they had already buried their savings to hide them. After all, citizens have always done this when looting was imminent. However, Cassius announced that anyone who knew of any treasure need only inform him. In return, the person would receive 10% of the confiscated property or, if they were a slave, freedom. According to Appian, this threat worked. After all, many rich Rhodians had not dug the holes where their treasures were buried themselves – their slaves had done so. For fear of being betrayed, they brought their treasures to Cassius. And Cassius was delighted to receive the impressive sum of 8,000 talents from the private property of the Rhodians alone.

An Aureus Made of Rhodian Gold?

Cassius probably had the looted treasure minted immediately into coins so that he could pay the soldiers. Bernhard Woytek, in his comprehensive work on Roman economic history from 49 to 42 BC, dates the Crawford 500/6 issue to the period immediately after the looting and before Brutus’ victory over the Lycians. After all, Brutus does not yet bear the title in of Imperator on this coin, which he later assumed at the meeting in Sardis in mid-42 BC.

On 30 October 2024, Künker is offering a magnificent aureus from this historically exciting issue at an estimate of 100,000 euros in auction 416. The about extremely fine piece was purchased on 12 September 1969 at Spink & Son in London.

The mint master in charge of this issue was Publius Cornelius Lentulus Spinther, who served as legate under Cassius. In the spring of 42 BC, he supervised one of the two mints in Asia Minor that produced Cassius’ coins.

At first glance, the depiction seems to be quite generic. One side shows the curved staff and the jug – the insignia of the augur, an office that Legate Spinther had held since 57 BC. The other side seems to represent Brutus’ office as pontifex. The assassin of Caesar had probably been part of the College of Pontiffs since 51 BC. We can see the insignia of an axe, a culullus and a knife.

Knowing that these coins were intended to be given to legionaries going to war, one might wonder why Cassius did not opt for a theme more suited to a military campaign – like a depiction of Victoria or Virtus. And why did Cassius decide not to depict Libertas, the freedom-giving deity who frequently appeared on his coins on other occasions?

Bull decorated for sacrifice. KHM, Vienna. Photo: KW

A Matter of Motivation: You Are Fighting for a Just Cause!

To understand this, we must keep in mind that the concept of a “just war” played an important role in ancient Rome. According to belief, the gods would only grant victory to those whose cause was just. This involved not only moral justification, but also included the meticulous observance of all the religious ceremonies that were associated with warfare.

Before every war, and even before every battle, the will of the gods had to be determined through the interpretation of an omen. This was the task of the augur, who observed and interpreted the omens on behalf of the commander. If no augur was available, the commander himself took on this role. In general, people were content with a minimum of effort in times of war. It was enough to take some chickens and feed them a small cake. If they ate it, you could be sure to have the approval of the gods. We might laugh at this today. Perhaps we would rather see a divine message in the fact that the chickens did not peck at every crumb. Nevertheless, no Roman would have dared to do without observing the omen, let alone act contrary to it.

Once the gods had approved of the commander’s intentions, the latter made a vow to Jupiter, but would not act on it until after the victory. When we talk about Roman triumphal processions today, we tend to forget that they were actually nothing more than a glorified walk to the capitol in order to offer a promised sacrifice. The ritual tools a commander needed for this were the culullus, used to pour water over the animal, a knife to cut off a tuft of its hair to throw it into the altar fire, and an axe to kill the animal – exactly the three insignia that we can see on the coin.

We can assume that these symbols and rituals were much more familiar to Roman soldiers than they are to us. When they looked at the coin, they will have immediately thought of the augurium and the victory celebration. And therefore the message of this coin is that the war of Brutus and Cassius is one that is deemed just by the gods and one that will be granted victory.

We know today that victory and defeat have nothing to do with whether a cause is just or not. History is written by the victory anyway, and no victor has ever admitted that his cause was a bad one. In any case, at the Battle of Philippi, fought in October 42 BC, Cassius was defeated and committed suicide. Brutus was initially victorious, but was defeated in a second battle and killed on the run. The resistance of Caesar’s assassins was crushed. But the struggle for power in Rome had only just begun.

Jochen Bleicken, Augustus. Eine Biographie. Berlin 1998

Ernst Künzl, Der römische Triumph – Siegesfeiern im antiken Rom. Munich 1988

Bernhard Woytek, Arma et Nummi. Forschungen zur römischen Finanzgeschichte und Münzprägung der Jahre 49 bis 42 v. Chr. Vienna 2003

By Ursula Kampmann on behalf of Künker