The die cutting czarina

11. May 2016 14:48

The medal of Czar Alexander I, honoring him as “savior of the people”, and issued in three metals – gold, silver, bronze – is stunning. On the reverse it shows an altar, on which the Russian insignia, crown, scepter, and imperial orb are placed. Above all, the Eye of Providence in the aureola is glancing down. The inscription “To Alexander the blessed” is engraved into the front of the altar. Three wreaths are lying at the base of the altar sacrificed to the heroic czar: in the middle there is the laurel wreath of the victor, to the left the wreath of peace made of olive branches, and to the right an oak wreath for saving people’s lives. The date on the medal, March 19th, 1814, doesn’t correspond to the year of issue of the medal. It refers to the glorious entry of the victorious Allies in Paris. But do not wonder, why this historical event, according to the medal, took place on March 31st – keep in mind that the Russians at the time followed the Julian calendar. And Maria Feodorovna, whose name is inscribed below the floor line of the altar, thought Russian, even though she was born in Germany in 1759.

From Künker Auction 277, Lot 345: Gold medal in the weight of 48 ducats of Maria Feodorovna on her son’s entry in Paris. This specimen, coming up at the next Künker summer-auction, is estimated at 125,000 euros.

Sophie Dorothea, as her baptized name was, was the fourth of the twelve children of Frederick Eugene of Württemberg, who later, a long time after her marriage, became Duke of Württemberg. Her mother was the grand daughter of a sister of Frederick the Great, which is why Frederick used an enquiry of the Russian Czarina Catherine to marry his great grand nice off to Paul, heir to the Russian throne, and therewith getting Prussia closer to Russia. For this, Sophie Dorothea had to convert to the orthodox faith and take on the name Maria.

Portrait of Maria Feodorovna at the age of 18 from Alexander Roslin.

Eremitage. Source: Wikipedia.

What Frederick underestimated was Catherine’s dislike for her own son. Paul was systematically kept away from all governmental affairs. And this dislike for Paul also conveyed to the young Maria Feodorovna, who wholeheartedly backed her husband. In 1783 Catherine had given them a castle in Gatchina, and this is where the young couple spend most of their time.

Their biggest problem was boredom. While Paul was drilling his unit of soldiers built up in accordance to the Prussian army system, Maria devoted herself to her artistic inclinations. She played the harpsichord, sang and painted watercolors – just like most of the well-behaved young ladies. Quite unusual was her profound interest in engraving. She designed cameos, worked herself with carving knifes to create works in ivory, and at an unknown point in her life she learned the craft of a medalist. In Nagler’s History of Arts we can read that Carl von Leberecht, who served at the Russian mint as a medalist since 1776, bragged that “an Empress was under his pupils, that is the Empress Mother Maria Feodorovna.”

While soviet historians could not imagine (or weren’t allowed to) that a Czarina was able to do something meaningful, today’s historians assume that Maria Feodorowna did have the skills to design medal dies. And we do know about a work shop, which she installed in her later years in Pavlovsk. It is there, where the “steel matrices displaying emblems of mythology” and “different coining dies” were stored.

Maria Feodorovna certainly did have enough time to learn a craft during her long years in Gatchina, when Paul and her were reduced to doing nothing. And in the 18th century it wasn’t that unusual for a member of high nobility to be a craftsman in his leisure time. The opera Czar and Carpenter, for example, is based on the fact, that Peter trained as a carpenter. Louis XV of France worked the wood lathe, and Louis XVI worked as a black smith in the royal smithy. And they were not the only ones. So, Maria Feodorovna chose to spend her time learning to cut stones and dies, which is why she went into training with Carl von Leberecht.

From Künker Auction 277, Lot 346:

Bronze medal of Maria Feodorovna on her son’s entry in Paris. The estimate of this piece only amounts to 500 euros.

Of course, a Czarina did not create coin dies for every day strikings. But, as a German and mother, the victory of her son Alexander I over Napoleon was worthy for creating dies with her own hands displaying this success. We know of two different die pairs for this medal, whose designs deviate slightly.

When she was named full and honorary member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in the presence of the Prussian King Frederick William III on December 26th, 1818, she subsequently – as required in the bylaws of the Academy – provided an entrance piece. And this piece was the medal, which she created to honor her son’s victorious entry in Paris.

Maria Feodorovna died on November 5th, 1828 in Pavlovsk. Just shortly before her death, she was able to read about herself, the “skillful princess”, in Nagler’s Encyclopedia of Artists.

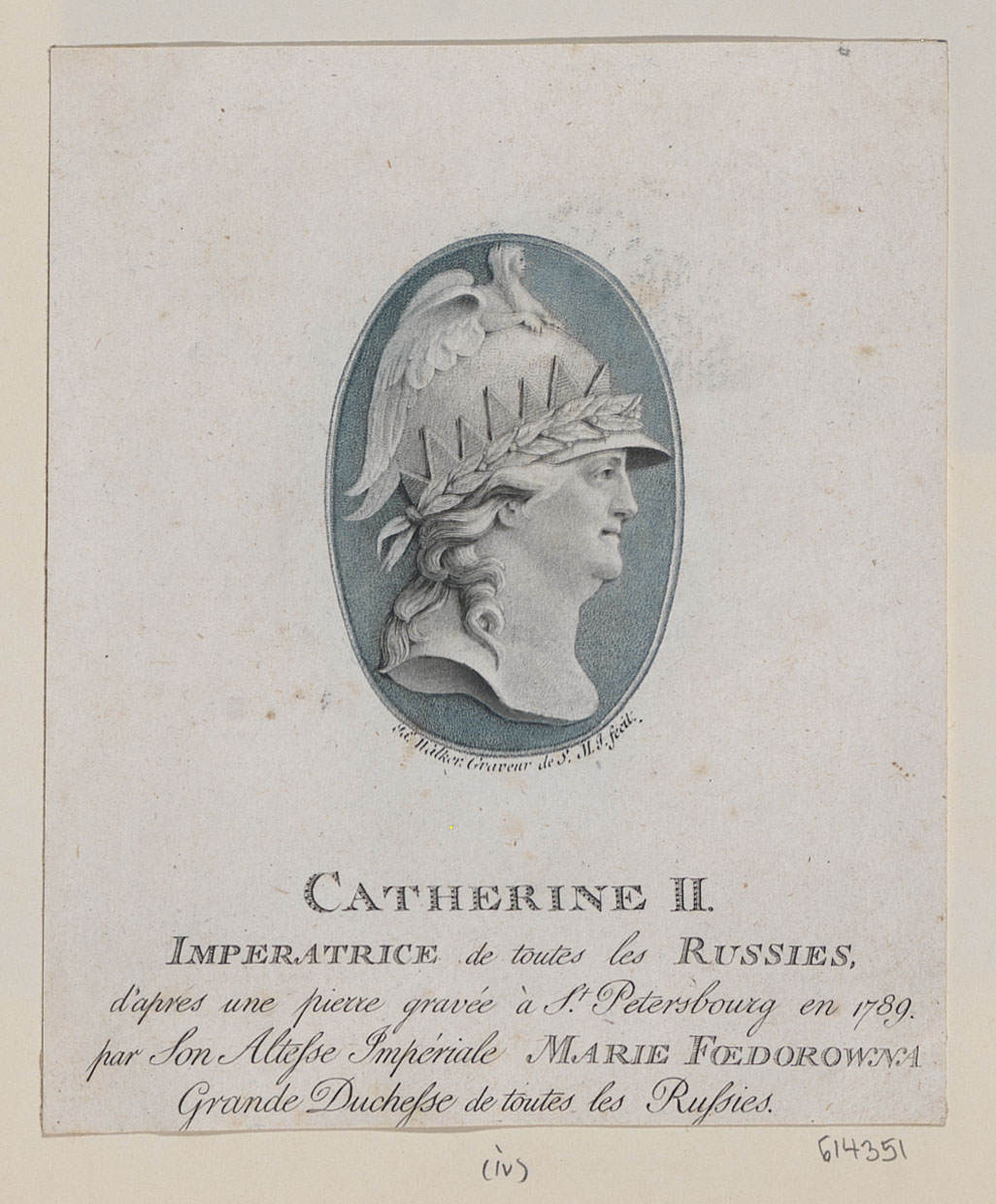

Gem with the portrait of Catherine II as the Russian Minerva,

made by Maria Feodorovna. Source: Wikipedia.